Bloodshot eyes in dogs can signal allergies, conjunctivitis, dry eye, corneal ulcers, foreign bodies, glaucoma, or uveitis. Learn urgent warning signs and sa...

Article

•

Designer Mixes

Cherry Eye in Dogs: Causes and Surgery Options

Shari Shidate

Designer Mixes contributor

Seeing a pink or red “bubble” in the inner corner of your dog’s eye can be alarming. As a veterinary assistant, I have talked with many worried pet parents who think their dog’s eye “popped out.” The good news is that cherry eye is common, treatable, and most dogs do very well with the right care.

In this article, we will walk through what cherry eye is, why it happens, when it is urgent, and the most common surgical options your veterinarian may recommend.

What is cherry eye?

Cherry eye is the everyday term for a prolapsed gland of the third eyelid. Dogs have an extra eyelid called the third eyelid (also called the nictitating membrane) that sits in the inner corner of the eye. Attached to it is a tear-producing gland.

When the tissue that normally holds that gland in place becomes weak, the gland can slip out of position and become visible as a round, pink to red swelling. It often looks like a small cherry, which is how the condition got its name.

Why that gland matters

This gland is not “extra.” It contributes a significant portion of the watery tear film (you may see sources cite roughly 30 to 50 percent). If the gland is damaged or removed, your dog may be more likely to develop dry eye (keratoconjunctivitis sicca), a chronic condition that can be uncomfortable and may require long-term medication.

What causes cherry eye?

The most common cause is weak connective tissue that fails to keep the gland anchored. This is often related to genetics, which is why cherry eye is seen more in certain breeds.

Breeds often affected

- Bulldogs (English and French)

- Cocker Spaniels

- Beagles

- Boston Terriers

- Pugs

- Shih Tzus

- Lhasa Apsos

- Mastiff-type breeds (including Cane Corsos and Neapolitan Mastiffs)

- Other dogs with short noses or prominent eyes

Cherry eye is also more common in young dogs, often under 2 years old, but it can happen at any age. Any breed can be affected.

Can it happen suddenly?

Yes. Some dogs wake up with it. In other cases, it appears after irritation, rubbing at the eye, allergies, or conjunctivitis. These issues may not be the true root cause, but they can increase swelling and make a weak gland pop outward.

Cherry eye can affect one or both eyes. Some dogs start with one eye, then the other eye prolapses weeks or months later.

Signs of cherry eye

- A pink or red mass in the inner corner of the eye

- Watery discharge or increased tearing

- Redness of the eye or conjunctiva

- Pawing at the face or rubbing the eye on furniture or carpet

- Squinting or holding the eye partially closed

Sometimes the gland slips back in on its own and then pops back out again later. Even if it comes and goes, it is worth a veterinary visit because repeated exposure can lead to irritation, infection, and gland damage.

Is cherry eye urgent?

Cherry eye is usually not a life-threatening emergency, but it should be evaluated promptly. In many cases, that means scheduling an appointment as soon as practical, often within a few days. The longer the gland stays out, the more swollen and irritated it can become, which may make repair more difficult.

Go the same day if you see

- Severe squinting or obvious pain

- Cloudiness or a bluish haze on the cornea

- Bleeding, or thick yellow or green discharge

- Your dog cannot open the eye

- Concern for trauma (a scratch, poke, or fight)

These signs can indicate a corneal ulcer or other serious issues that need immediate treatment.

How vets diagnose it

Diagnosis is usually made with a basic ophthalmic exam. Your veterinarian may also do:

- Fluorescein stain to check for corneal ulcers (especially if your dog is squinting)

- Tear testing (Schirmer tear test) if dry eye is suspected

- Eye pressure testing in some cases to help rule out other eye problems

It is important to confirm it is truly cherry eye and not a tumor, cyst, eyelid abnormality, or another mass in the corner of the eye, especially if it is firm, irregularly shaped, or not the typical smooth, round swelling.

Can it be treated without surgery?

Sometimes, early cases can temporarily improve with medications such as anti-inflammatory eye drops or ointments, plus preventing rubbing with an e-collar. However, in most dogs, the gland will prolapse again because the underlying issue is mechanical (weak attachment).

Non-surgical management may be considered when:

- The prolapse is very mild and recent

- Your veterinarian wants to reduce swelling before surgery

- Your dog is not currently a good anesthesia candidate and needs stabilization first

If your dog has cherry eye, you will often hear the recommendation: repair, do not remove, whenever possible.

Surgery options

There are a few surgical techniques, and the best choice depends on your dog’s anatomy, how swollen the gland is, whether this is a first-time prolapse, and your veterinarian’s experience. Many general practice veterinarians perform cherry eye repair, and complicated or repeat cases may be referred to a veterinary ophthalmologist.

1) Pocket technique

This is one of the most common approaches. The surgeon creates a pocket in the tissue of the third eyelid and tucks the gland back into its normal position, securing it with sutures.

- Pros: Preserves the gland and tear production, widely used, good success rates.

- Cons: The gland can re-prolapse in some dogs, especially certain breeds.

2) Tack technique

In a tacking procedure, the gland is anchored back into place by suturing it to deeper tissues near its normal location.

- Pros: Can be helpful in some recurring cases or specific anatomies.

- Cons: Depending on technique, may have a different risk profile for irritation or recurrence.

3) Combination repairs

Some surgeons use a combination of pocket plus tacking methods, particularly for dogs with repeat prolapse or very loose tissue.

4) Gland removal

Removing the gland was more common years ago, but it is now typically avoided because it can increase the risk of dry eye later in life.

- When it might be considered: If the gland is severely damaged, necrotic, or has chronic disease and cannot be salvaged, or if multiple repairs have failed and the dog’s comfort is at stake.

- Important note: If removal is discussed, ask about long-term dry eye monitoring and expected ongoing care.

Recovery and aftercare

Most dogs go home the same day. Recovery instructions vary by clinic, but commonly include:

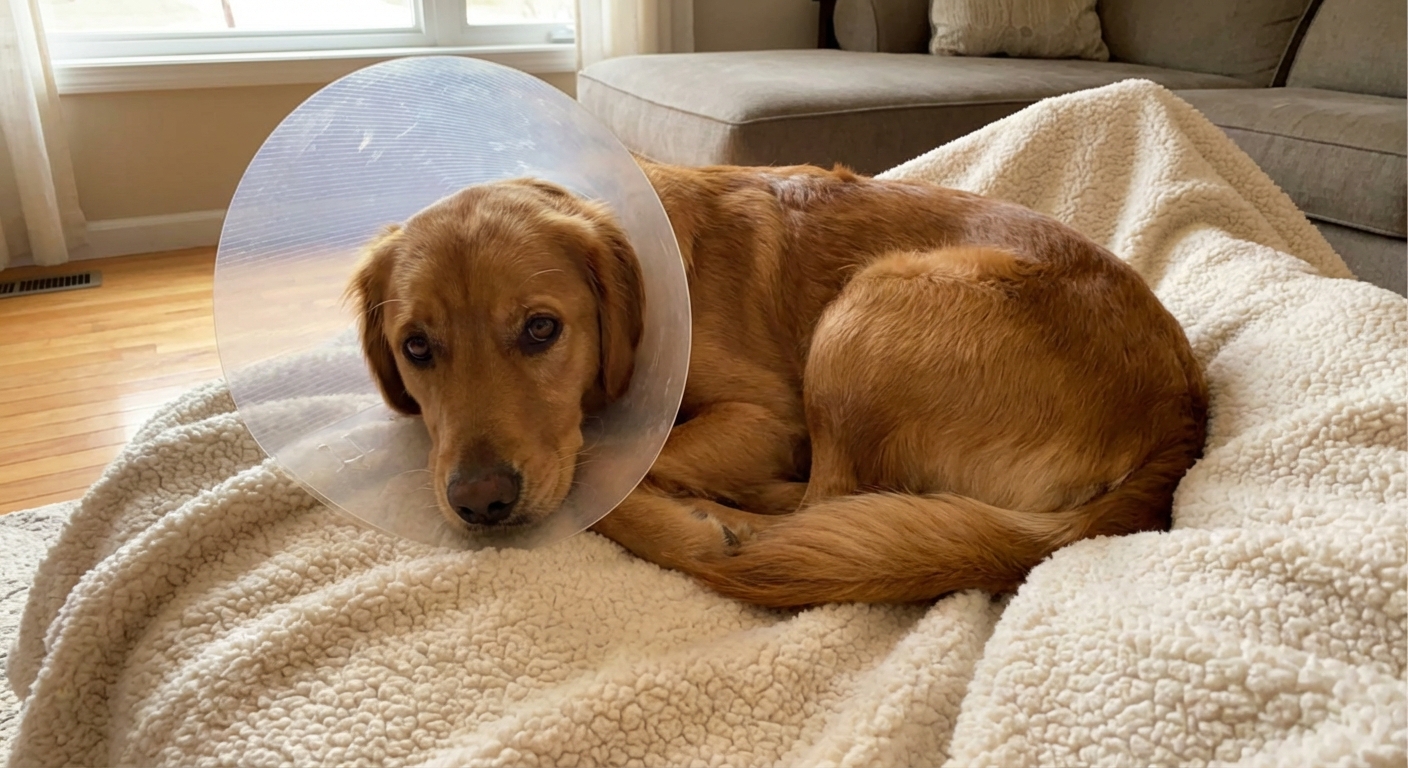

- E-collar (cone) nearly all the time for 10 to 14 days to prevent rubbing

- Eye medications such as antibiotic ointment, anti-inflammatory drops, or lubricants

- Activity restriction to reduce face rubbing and play injuries

- Recheck visit to ensure the gland stays in place and the eye surface looks healthy

Many repairs use absorbable sutures. You may still see mild redness, swelling, or a small amount of discharge early on. Worsening discharge, squinting, or signs of pain are not normal and should be reported.

When will my dog look normal?

Mild swelling and redness can persist for days to a couple of weeks. Many dogs look dramatically better within the first week, but full healing takes time.

Problems to watch for

- Re-prolapse (the gland pops out again)

- Eye discharge that increases instead of improves

- Squinting or apparent pain

- Corneal ulcer from rubbing or suture irritation

- Dry eye, especially if tear production was already borderline

If you notice worsening redness, squinting, or your dog seems uncomfortable, call your veterinarian quickly. Eye issues can change fast.

Other pets and people

Cherry eye is primarily a dog condition. It can happen in cats, but it is uncommon. People do not get cherry eye.

Costs and planning

Cherry eye surgery costs vary widely by region, clinic, and whether an ophthalmologist is involved. Your estimate may also change based on testing needed (like a corneal stain) and medications for recovery. If cost is a concern, ask your clinic what is included and what options are available.

Prevention and outlook

You cannot always prevent cherry eye, especially when genetics are involved. What you can do is act early and protect the eye.

- Do not let your dog rub their face on carpet or furniture

- Use an e-collar if needed until your appointment

- Avoid trying to pop it back in at home unless your veterinarian specifically instructs you, because pressure or accidental scratching can injure the cornea

- Keep up with follow-ups and tear testing if recommended

The outlook is generally excellent when the gland is repaired and protected. Many dogs live perfectly normal lives after surgery, with healthy eyes and comfortable tear production.

If you take away just one thing, let it be this: cherry eye looks dramatic, but in most cases it is very treatable, and preserving the gland is usually the healthiest long-term choice.

When to call your vet

Call your veterinarian if your dog has a new red mass in the inner corner of the eye, even if it seems mild. Seek urgent care if your dog is squinting, the eye looks cloudy, or there is thick discharge.

If you are unsure, it is always okay to send a photo to your clinic and ask if your dog should be seen right away. In eye care, earlier is often easier.